The World's finest

Montecristi

Panama Hats

Built on Trust

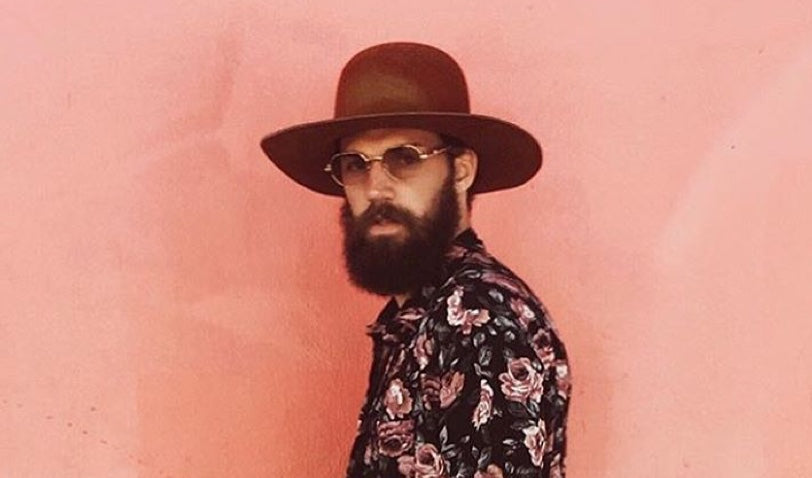

Orlando tells the tale in his own voice.

I took most of this footage during my visits to Pile, Ecuador. Pile is a small village located 30 km (about 19 miles) away from Manta, the nearest large city. Citizens of Pile have been weaving hats for over 400 years—their economy is mostly sustained by harvesting toquilla straw, hat-weaving, farming, and tourism. It’s one of the last places in Ecuador where Montecristi Superfino Panama Hats are handwoven, and since the early days of Worth & Worth, I have been fortunate enough to work side by side with some of the great master weavers of Pile.

My first visit to the village was in 1995, one year after we met Don Rosendo, a master weaver even then. We had built a trustful relationship, and asked if we could visit the birthplace of his magnificent hats. He kindly agreed. We set off on our journey at 9 AM; the day was still early by American standards, but by Ecuadorian time it was half gone. We traveled along a dirt road covered in watermelon-sized potholes; when we pulled up, we were amazed to see that all of the houses were built on bamboo stilts.

There, Don Rosendo introduced us to Don Raul Alarcón, who sized us up before bringing us into his home.

Religious icons covered the walls inside, and something in the corner caught my eye. Wrapped in cotton cloth, and held up by a three-pronged trunk called a mula, was a gem of long strands of fine straw, much like the hair of the indigenous women we had seen hiking up the Andes.

I asked Don Raúl if I could take a closer look. He smiled and unveiled a piece so tightly woven, it seemed it could hold water.

At that moment, in walked Doña Carina: Don Raul’s wife, a woman with piercing brown eyes, a firm handshake, and a demeanor that could calm a charging tiger. She gently approached the mula, unwrapped a half-woven hat, and—with thumbnails that sharpened to a point like a Japanese knife—commenced to weave.

First, she wet her hands from a small bowl that sat to the left of the mula. Then she stroked the fibers softly, caressing the strands of toquilla like a mother conditioning her child’s hair. Her dexterity, her speed, and the fluidity and concentration with which she wove was otherworldly, and I found my own mind in another realm. She whipped and pulled and organized those hundreds of strands with the concentration I would expect of a NASA mathematician. “Fascination” could not touch what I felt.

What I understood as a fellow craftsperson was the sense of process and flow: everything else around us became white noise

What I understood as a fellow craftsperson was the sense of process and flow: everything else around us became white noise. We sat in the room together in a state of zen, until someone would tell a humorous story. We would all laugh, and then return to zen. It was peaceful, with none of that senseless, nervous chatter of wanting to hear yourself...it was pure, a meditation.

We understood each other. We have built more than a business relationship—they became part of the family. Through the years of our relationship we have built a clinic and a school in Pile. I recognize the simplicity, the craft, and we live a truth built on trust.

Orlando Palacios

Contrary to its famous name, the Panama hat has always been woven in Ecuador. Hats exported in the 1800s were first transported to Panama, before setting sail for the United States, Asia, & Europe. From then on, these finely plaited “straw” hats were referred to by their port of origin. The highest quality—and most expensive—Panama hats are woven from the leaves of the toquilla palm, and made in the region of Manabí.

Read MoreA Passage of Rites

Artisans, who have this craft in their DNA from centuries of weaving, create the world’s finest Montecristi Panama hats.

The weaver harvests selected fronds of “tallos”—blades of toquilla palms. Almost 50 are needed to make a single hat.

Delicate strands are used for a superior tight weave. The tallos are stripped and boiled, before being dried and bleached.

The Montecristi Panama hats are

made by a centuries-old process

The process of creation is very involved; labor is split between seven craftspeople: weaver, backweaver, tightener, cutter, bleacher, ironer, & hatmaker.

Weaving begins by creating a small cross of eight strands, then exponentially adding eight more until the plantilla has formed.

For Montecristi Superfinos, a single

fiber may be split 4 times

This step of the process is painstaking, and can take three months up to one year. Like a precious jewel, the hat passes from one hand to the next.

For a month, the plantilla is placed on a wooden block, to shape the hat as it is woven.

Once weaving is complete, the hat is thoroughly washed, line-dried, then again smoked and bleached in a sulphur box.

It all starts with these strands,

which turn into works of art

A strand of this caliber is thinner than dental floss—anywhere between 1,500-3,000 strands are woven into one hat.

Hold it to the light and it glows, seemingly translucent.

And finally the hat is passed to Orlando’s hands in New York City, where it is steamed, hand-blocked, and caressed over the hat-shaping block into its final desired form.

Our Master Weavers

The weavers work in the cool of tropical mornings and evenings; they don’t want sweat from their hands staining the toquilla palm-fiber “straw” used to make the Panama hat, for which Ecuador’s Montecristi region is famous.

Decades ago, it is said 2,000 weavers lived in Montecristi; now there are fewer than 200. Of these, perhaps 15 have the skill to fashion the finest Panama hat, the silky Montecristi Superfino.

Collaborating in Community

100% Thanks to your generous contribution we have reached our goal of raising $8,000.

We will keep you updated those upcoming weeks on the project.

And we never stop giving back!

“When I asked the people what they wanted, if they wanted food or clothing they said, “‘Food would rot, clothing would waste, but a clinic would stand.’” So it became Orlando’s dream to build a clinic in Pile, providing free medical care for this community of master weavers.

Read moreWe are proud to carry the most exquisitely-crafted Montecristi Panama hats in the world. Depending on the plait’s caliber, a Montecristi Panama hat can take up to a year to weave. Available in ARTISAN, MASTER, MUSEUM, and SUPERFINO, our hats have a soft texture, translucent appearance, and luminous ivory color.

Read more